Personally, I've only installed the LUT for the Node Graph viewer because:

- Compositing is the most important place to maintain proper color management.

- I know how to install it in the Node Graph viewer because it's the "Nuke" half of the application and Hiero is more difficult to customize.

- It was a pain in the ass to do it once and I don't feel like doing it a second time.

The unfortunate result is that my footage looks different in the Node Graph viewer and the Timeline viewer. Which sucks, but since I'm not doing any color work in the Timeline, and I made sure my footage was properly color-managed when I was doing the compositing work in the Node Graph, I know it'll look right when I move everything to Resolve.

Color Correction

When the VFX work is complete and the sequence is ready to be color corrected, I export an XML of the timeline from Nuke Studio. Why an XML instead of an AAF like the one I exported from Avid? Because, while Nuke Studio is capable of importing AAF, XML, and EDL files, it's only able to create XML and EDL files.

No, I don't know why.

And, since Avid can only create AAF and EDL files, I have to use 2 separate "professional file interchange formats" in my workflow. Makes total sense.

EDL is out of the question because it's the oldest of all exchange formats, with the fewest features, and a separate EDL has to be created for every video track in a given timeline. No thank you.

Resolve typically imports and relinks the XML without any issues. It does, however, fail to recognize that the EXR sequences have handles, so the vfx shots need to be slipped 12 frames in the timeline before proceeding to color correction.

A Question for the Audience

Being that all of our footage is Alexa LogC footage, at some point, as part of the color correction process, we should be using Resolve's built-in 3D Alexa LUT to linearize the footage and convert it to monitor-space. But, if you recall from earlier, Resolve doesn't separate the linearization LUT from the viewer LUT like Nuke does. So the question is do we apply the LUT to the clips in the Media page before color correcting, or as a Node on the Color page? Should it be the first or last Node on a Shot? Or added to the Timeline so all clips can be corrected with one global Node? Some of those options affect preview thumbnails in the app. Does that bother you?

Clearly, I'm not sure of the correct answer. I've found that, no matter which option I choose, the results are questionable.

Ideally, we would linearize the footage prior to performing any color transformations so our math is correct, then we'd use a viewer LUT to view the tone mapped image in monitor-space. Just like Nuke does. But, again, we don't have those kind of tools in Resolve (by default). This is not simply an issue of semantics. While it's possible to arrive at the same final image, regardless of the order in which you add the LUT, getting it backwards will adversely affect the experience of using the color correction tools.

Adding the LUT before color correcting makes the Color Wheel tools in Resolve sensitive to the point that small color changes are near impossible. Which is understandable when you think about it. The wheels are expecting an input image with linear values across a certain range. When the values are compressed with an inverse-Log gamma curve, they will not change as you'd expect them to when you move the color wheel.

And this goes for almost any color space in any color correction tool. If you've ever had the experience of dragging a color wheel or slider and seen the image change much more dramatically than you expected, chances are the color tool was expecting a different gamma or color space than the image being fed into it.

Which is why, while a pain in the ass to use, the 2-step process of linearizing Alexa footage in Nuke is necessary to apply mathematical operations correctly. It's too bad Nuke's color correction tools are a bigger disaster than Resovle's LUT issues.

Regardless, this issue is the reason I was hesitant for a long time to make Resolve my primary color correction application. It has a (mostly) fixed UI and I found the small size of the color wheels and sliders frustrating to manage with a mouse or Wacom pen. But my frustration was due almost entirely to the sensitivity created by using incorrect LUT settings on my clips. When clips are correctly color managed, Resolve's color tools are much easier to use. Not great, but easier.

This is why, up until this year, I color corrected my projects in After Effects with Red Giant Colorista. I love Colorista. Love it. Its color wheels are dampened for smooth adjustments and include fast, easy to use tools for HSL adjustments that are a dream to work with. The reasons I went in search of a dedicated color correction application like Resolve had nothing to do with Colorista's toolset, and everything to do with my frustrations with After Effects.

Back to Color Correction

Assuming we've struggled our way through the LUT and interface difficulties and created a color corrected image we're happy with, the next step is to export the clips.

Depending on the project, this step will vary. If all work on the "picture" portion of the video is now complete, a single 1080p ProRes 4444 QuickTime file will be rendered of the entire sequence.

If the project requires Motion Graphics work that I either couldn't, or didn't want to create in during the VFX stage, each shot will be rendered as a separate ProRes 4444 QuickTime file.

The clips are rendered into their own subfolder, with their original names plus some sort of modifier appended to the filename, indicating they are the color corrected versions of the clip (typically _CC). As long as the names are consistent, they're easily relinked to an XML with Nuke Studio's bevy of conforming tools.

Motion Graphics

Assuming this is a project that needs Motion Graphics work, the individually-rendered shots are re-conformed into a sequence in one of two possible applications.

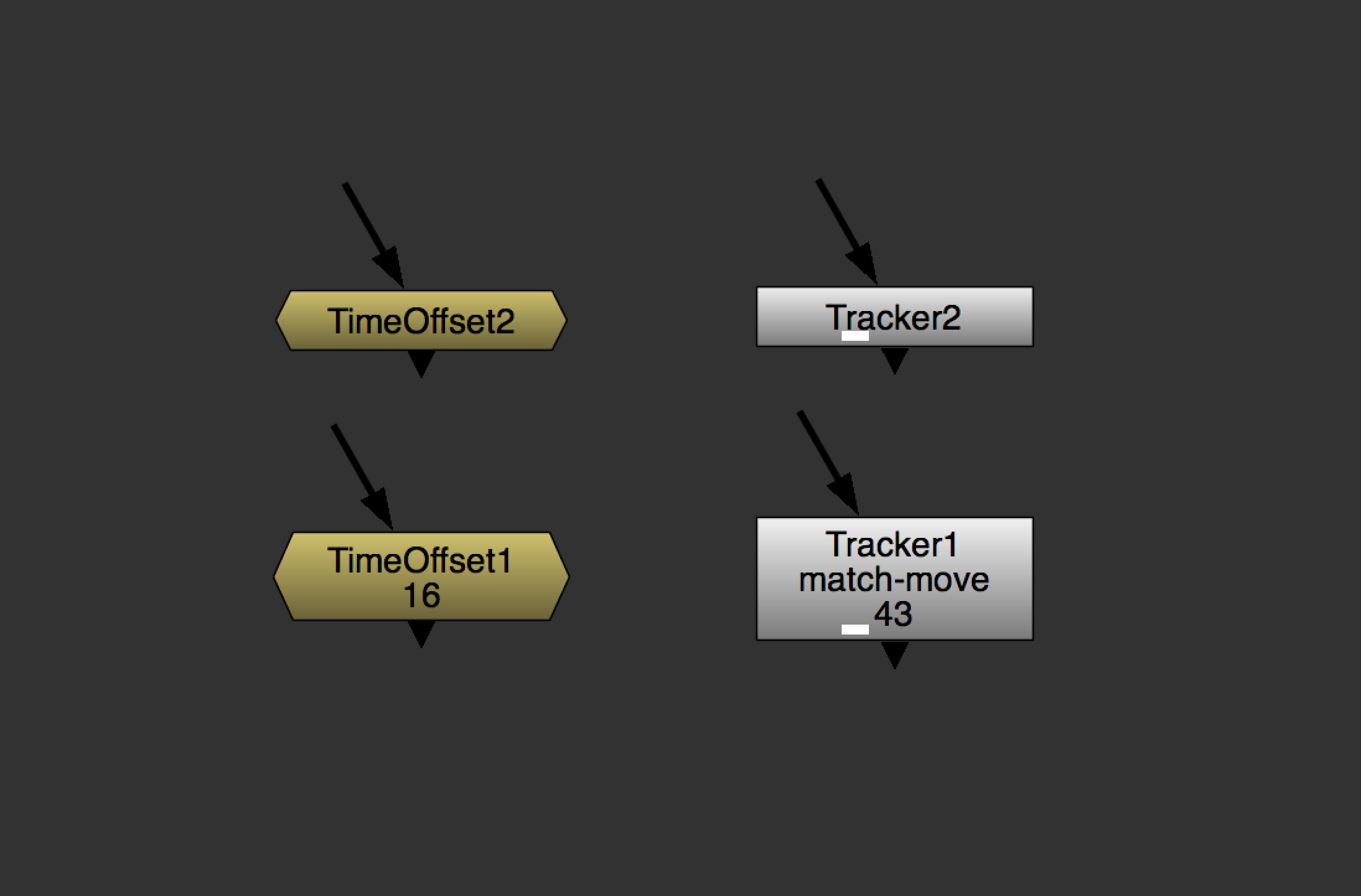

If I can do the work in Nuke, I will. Nuke isn't necessarily built for motion graphics, but it is my app of choice for most tasks. And, with the addition of my Node Sets gizmos, it's not as difficult to coordinate complex animations as it once was. The color-corrected QuickTimes are conformed back into Nuke Studio with the Build Track tool, and work begins, similar to VFX phase of post.

There are, however, certain motion graphics tasks that are better suited to being completed in After Effects (read: anything to do with text). In which case the XML that was previously imported into Resolve is imported into After Effects using the Pro Import After Effects option, formerly known as Automatic Duck. The sequence comes in offline, and each clip is manually relinked to the corresponding color-corrected file.

Yes, I could conform the color-corrected plates back into Nuke Studio and generate a new XML that references the color-corrected plates in order to save myself the hassle of manually relinking incorrectly named clips in AE but, more often than not, that method fails to reconnect all clips and manual relinking is needed anyway so I save myself some time and go straight to manually relinking.

I've also experimented with importing and relinking the XML in Premiere, thinking the NLE would have better luck relinking the clips than the compositing application, in which case I could use Send to After Effects to get it into AE. More complexity, more idiosyncrasies, more failures, more time wasted.

Once motion graphics work is completed, our picture should be locked. A single ProRes 4444 QuickTime file is rendered of the final timeline. This is one instance where I prefer to be working in After Effects. Though AE's renderer can be slow and is not without the occasional glitch, its stability and speed are miles ahead of Nuke Studio, especially with regard to QuickTime files.

By my estimation, the number of successful QuickTime renders I've created with Nuke Studio is likely a single digit percentage. And the time taken to perform the render is somewhere between 2x and 10x the amount of time of other applications.

I recently tried to use Nuke Studio to create dailies instead of using Resolve. The estimated time to create ~20 minutes of dailies was 12 hours and the render failed on the first clip. Resolve knocked out the render on the first try (after correcting the pixel aspect ratio) in less than 30 minutes.

Have I mentioned that Resolve is free and Nuke Studio costs $10,000. I think it's worth mentioning again. Resolve is free and Nuke Studio costs $10,000.

Sound

With picture locked and rendered, now it's time to work on sound. Our original AAF file from Avid is imported into Final Cut Pro 7 with Automatic Duck. Yes, just like FCP 7 itself, the Automatic Duck plugin still works.

The sequence that comes in is our offline edit, but with the original WAV files I manually conformed in Avid prior to the AAF export. The ProRes 4444 file of our finished picture is imported and lined up with the offline timeline. Once aligned, all the offline video tracks are deleted, leaving just the final picture file and the offline audio. Using Reconnect Media, all audio clips are relinked to their original files.

One hiccup I frequently run into is the naming convention used by whatever audio recorder my sound recordist uses on set. The CF card he hands me on set is full of WAV files with names like 12T03. That is, Scene 12, Take 3. For some reason, the metadata for that file is named 12/03. I assume the / isn't in the file name because whatever file system the recorder is using doesn't play nicely with having a forward-slash in the name.

While I'm sure there's probably a way to have the recorder use the same file name in both places, what this issue requires of me in post is that I batch rename a copy of the original sound files, replacing the T with the / that FCP is searching for. For this task I use Name Mangler, but it could just as easily be done with OS X's batch renaming tools.